HORSES AND MOVEMENT from PAINTINGS and DRAWINGS

by Lowes Dalbiac LUARD

With a Note on the Drawing of Movement, by the Artist, and a Foreword by MARTIN HARDIE

An Introduction by ArtGraphicA

Horse Art.

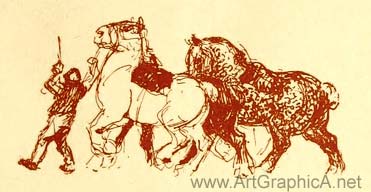

Horse Art.Lowes Dalbiac Luard was an English artist and expert in horse art and anatomy. Luard had studied in Paris and was captivated by the sights of Percheron horses (a breed of draft horse from Northern France), moving heavy loads of stones and timber in the French capital during the early 1900’s.

During his 30 year stay, Luard painted oils and undertook drawing studies, capturing the activity of horses in Paris bearing heavy loads by the banks of the Seine river. Their sheer power and movement enthralled Luard who was able to capture their rhythm and beauty quite unlike any other artist before him. He seemingly shunned any artists’ total dependency on photography to capture their movement, stressing the importance of observation to portray their dynamism, devoid in that of the mechanical camera.

When inevitably the workload of horses gave way to machinery, the artist took to observing and painting horses from the racetrack. Sadly Luard (who was famous in his own time) has been somewhat forgotten today and we associate horses and art more with the likes of Edgar Degas or George Stubbs.

Whilst this book does not teach the artist how to paint or draw horses, it does offer great insight into how we might better observe them, and provides great inspiration into really expressing the dynamism of their movement and actions without creating stiff and emotionally detached works of art.

FOREWORD

THE keynote of the paintings and drawings reproduced in this volume is Movement. Work so full of force and originality speaks for itself, but its interest is enhanced by an introductory article in which the artist explains what he maintains to be fundamental principles in the drawing of movement. " The words, Life is Movement," he once remarked in conversation, " should be in capital letters over the studio door. " And in a sense it is true, for even the massive and apparently immovable cathedral is obeying the laws of movement, gaining stability as the outcome of the balance of opposing forces thrusting and resisting. In this article Mr. Luard tells us also from a scientific point of view just how we are impressed by movement in nature, though he does not mean to imply that movement in Art needs to include all such impressions.

In his Introduction he speaks with so much authority and writes with so stimulating an appeal to every student of drawing, that one feels that any further preface is superfluous. If, therefore, I have the sense of trespassing on another man's private property, my excuse and justification must be my own admiration of Mr. Luard's work, and the hope that a fairly intimate knowledge of the artist and of his aims and methods may enable me to show how admirably these drawings embody the principles which he upholds. At any rate, it is possible for me to refer more directly to his work than the artist's own modesty would permit, and to emphasize the close relationship between Mr. Luard's theory of drawing movement and his own practice, as illustrated in what I feel to be the remarkable, and in many ways unique, series of paintings and drawings reproduced in this volume.

But first, for the benefit of students who are interested in these drawings, as they surely must be, something should, I think, be said as to Mr. Luard's own training and career, and I hope that the artist will forgive a critic, who is fully conscious that good wine needs no bush, for playing the showman.

Lowes Dalbiac Luard, as the name shows, belongs to an old Huguenot family of Norman-French origin, and it is interesting to note that one of the capitals in the Abbaye aux Femmes at Caen, from which town the family fled after the Edict of Nantes, was designed and carved by a Luard. It is clear that the family's artistic bent has always been strong and persistent. His grandfather, though a soldier by profession, was also a noteworthy artist. For sufficient testimony we may refer to his " Views of India " and his " Dress of the British Army," and more remarkable still, a series of water colours executed for a diorama of Indian life, which was painted in oils by Louis Haghe and shown at the old " Globe " in Leicester Square, and afterwards in America. Lowes Dalbiac Luard, as the name shows, belongs to an old Huguenot family of Norman-French origin, and it is interesting to note that one of the capitals in the Abbaye aux Femmes at Caen, from which town the family fled after the Edict of Nantes, was designed and carved by a Luard. It is clear that the family's artistic bent has always been strong and persistent. His grandfather, though a soldier by profession, was also a noteworthy artist. For sufficient testimony we may refer to his " Views of India " and his " Dress of the British Army," and more remarkable still, a series of water colours executed for a diorama of Indian life, which was painted in oils by Louis Haghe and shown at the old " Globe " in Leicester Square, and afterwards in America.

Mr. Luard's uncle, John Luard, also a soldier, became an artist, joined the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and for some time shared a studio with Sir John Millais. One of his Crimean subjects had so great a success at the Academy that it had to be railed off from the crowd. As Colonel Luard, R.E., his father, was also an extremely clever water-colour artist, it is hardly surprising that Art should have claimed Mr. Luard for her own. Mr. Luard's uncle, John Luard, also a soldier, became an artist, joined the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and for some time shared a studio with Sir John Millais. One of his Crimean subjects had so great a success at the Academy that it had to be railed off from the crowd. As Colonel Luard, R.E., his father, was also an extremely clever water-colour artist, it is hardly surprising that Art should have claimed Mr. Luard for her own.

Mr. Luard was born in India and educated at Clifton College, where the neighbouring Zoo was an unfailing attraction to a boy keenly interested in drawing living animals. But even before that time movement was his great interest. From the age of five he was constantly drawing horses, always in motion ; and family tradition tells how, when only eight years old, he actually lost his dinner one day through following a milkmaid carrying cans on a yoke, keenly alert to watch the balance of her pails and swing of her skirt, of which he afterwards made a complete water-colour drawing from memory. Even at that early age it never occurred to him not to draw a thing just because it was moving.

On leaving Clifton, he worked for a time at a class in Gower Street, conducted by Davis Cooper, son of Abraham Cooper, R.A. Passing to the Slade School, he studied under Professors Brown and Tonks. At the Slade, though he profited by close study of the figure, he was never really stimulated by the posed model. It was when the model rose from the throne, and moved naturally and freely, relaxed his limbs, and stretched his arms, that Luard began to draw with real interest and zest. He was not a School draughtsman.

His school was the world of real movement outside as recorded in the rapid and concentrated notes and memoranda made from quick observation in his own sketch books.

Though he settled down in London and painted a few successful portraits, it is obvious, from what has already been said, that ordinary forms of laborious portraiture could never be the first interest of such a temperament. In most of his sitters he found little to stimulate his artistic interest ; he felt again his instinctive dislike of the posed figure, though with children, who cannot pose, he was often particularly happy. He felt, rightly, that, as a rule, his first swift sketch in chalk conveyed more of vitality than the finished work in oil.

It was with this feeling that he determined, in 1904, to follow out a course of drawing in the studios of Paris. He went there intending to stay for three months ; he has stayed there ever since. It so happened that soon after he arrived the boulevard opposite to his flat was dug up for repair, and became monumente with the going and coming of carts and horses, the lift and heave of figures hammering and digging. Movement, as always, held him at once in thrall, but it was the French draught horse that really kept him in Paris. As he once remarked to me, the horse is interesting because it is the only real nude we can see daily at work. And here on the banks of the Seine, in all weathers and with untiring concentration, he would watch these splendid Percheron horses, which pull as much by energy as by weight, struggling up the steep slopes with their heavy loads of sand and stone. This it was that first inspired the characteristic series of subjects that have held him ever since, and have been shown year after year in his paintings and drawings at the New Salon in Paris, the Goupil Gallery in London, and elsewhere.

Subject and treatment are a matter of temperament. Ingres was all for pure and severe line. Chardin, to take another example, liked to sit and study and contemplate. Most people prefer the static to the dynamic, and Mr. Luard would grant that a picture representative of movement makes many people uneasy. He realizes that movement tends to make a picture restless, and that to many eyes repose has become one of the essential qualities of art. But Mr. Luard does not feel this any more than did such painters as Rubens, Goya or Millet.  He can paint a horse in a stable, a lamb browsing among buttercups, and paint them well, and for him they would be interesting studies enough, but unstimulating ; and he is right in letting the personal factor overcome impersonal facts. Was it Renan who said : " Le plus grand peintre n' apercoit dans le monde que ce qu'il aime y voir ; it y a une preference au fond de chaque talent? " He can paint a horse in a stable, a lamb browsing among buttercups, and paint them well, and for him they would be interesting studies enough, but unstimulating ; and he is right in letting the personal factor overcome impersonal facts. Was it Renan who said : " Le plus grand peintre n' apercoit dans le monde que ce qu'il aime y voir ; it y a une preference au fond de chaque talent? "

* The painter's problem is not to represent facts, but to express the feeling stirred in him by what he sees. It is not so much the man and the horse that interest Mr. Luard as the infinite variety of rhythm and music in the toil and struggle that express vitality and life.

The drawing of movement should appear inevitable and spontaneous, like the lyric in poetry. It must convey with rapidity the keen spell of some intense emotion or experience. The draughtsman's work must run to its end with a rush of swift decision, without halt or obstruction, and in its unity it must incorporate and express the unity of the experience which inspired it. Being, in this way, the direct result of creative impulse, it must be red- hot : it cannot be produced in cold blood. Ingres uses a line that is inevitable in its perfection, but a line which is opposed to the expression of movement. In his case it is an instrument forged and tempered by an artist of cold passion, whose instinctive preference was for patient searching observation, only possible of things at rest, one who from his heart hated the swirling Rubens and all his works.

* The really great painter has eyes only for what he wants to see in the world about him. At the root of all true talent there lies an instinctive preference.

LIST OF ART PLATES

- 1. CHESTNUT HORSES

- 2. UP THE BOULEVARD

- 3. COUP DE COLLIER

- 4. TOURNANT LE TOMBEREAU

- 5. PLOUGHING NEAR SALISBURY

- 6. CHARGING THE SLOPE

- 7. AT WATER : UP THE SEINE

- 8. TROTTING : PARIS BUS TEAM

- 9. BETWEEN THE STAGES : PARIS

- 10. ON THE TOP OF THE BANK

- 11. UNDER THE TREES (Colour)

- 12. HARROWING

- 13. UP THE RAMPE

- 14. TIMBER-HAULING ON THE SEINE

- 15. SPRINGING 'EM

- 16. A SUMMER SKY

- 17. THE SHIRKER

- 18. NIGHT WORK

- 19. THE BLACK HORSE

- 20. STONE-CART : BIRD'S EYE VIEW

- 21. TURNING THE CORNER : FRENCH STONE-CART

- 22. THE SUNNY QUAY

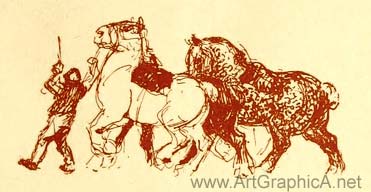

- 23. LED HORSES

- 24. DEAD BEAT : FRENCH ARTILLERY, THE SOMME, 1916

- 25. AN EFFORT

- 26. BACKING

- 27. ON THE HILL-TOP NEAR PARIS

- 28. FALLEN

- 29. BLOWN

- 30. SAND-CARTS

- 31. GUN TEAM IN A CRATER

- 32. THE SEINE : WINTER

Prev Page

Art Books

|

Lowes Dalbiac Luard, as the name shows, belongs to an old Huguenot family of Norman-French origin, and it is interesting to note that one of the capitals in the Abbaye aux Femmes at Caen, from which town the family fled after the Edict of Nantes, was designed and carved by a Luard. It is clear that the family's artistic bent has always been strong and persistent. His grandfather, though a soldier by profession, was also a noteworthy artist. For sufficient testimony we may refer to his " Views of India " and his " Dress of the British Army," and more remarkable still, a series of water colours executed for a diorama of Indian life, which was painted in oils by Louis Haghe and shown at the old " Globe " in Leicester Square, and afterwards in America.

Lowes Dalbiac Luard, as the name shows, belongs to an old Huguenot family of Norman-French origin, and it is interesting to note that one of the capitals in the Abbaye aux Femmes at Caen, from which town the family fled after the Edict of Nantes, was designed and carved by a Luard. It is clear that the family's artistic bent has always been strong and persistent. His grandfather, though a soldier by profession, was also a noteworthy artist. For sufficient testimony we may refer to his " Views of India " and his " Dress of the British Army," and more remarkable still, a series of water colours executed for a diorama of Indian life, which was painted in oils by Louis Haghe and shown at the old " Globe " in Leicester Square, and afterwards in America. Mr. Luard's uncle, John Luard, also a soldier, became an artist, joined the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and for some time shared a studio with Sir John Millais. One of his Crimean subjects had so great a success at the Academy that it had to be railed off from the crowd. As Colonel Luard, R.E., his father, was also an extremely clever water-colour artist, it is hardly surprising that Art should have claimed Mr. Luard for her own.

Mr. Luard's uncle, John Luard, also a soldier, became an artist, joined the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and for some time shared a studio with Sir John Millais. One of his Crimean subjects had so great a success at the Academy that it had to be railed off from the crowd. As Colonel Luard, R.E., his father, was also an extremely clever water-colour artist, it is hardly surprising that Art should have claimed Mr. Luard for her own. He can paint a horse in a stable, a lamb browsing among buttercups, and paint them well, and for him they would be interesting studies enough, but unstimulating ; and he is right in letting the personal factor overcome impersonal facts. Was it Renan who said : " Le plus grand peintre n' apercoit dans le monde que ce qu'il aime y voir ; it y a une preference au fond de chaque talent? "

He can paint a horse in a stable, a lamb browsing among buttercups, and paint them well, and for him they would be interesting studies enough, but unstimulating ; and he is right in letting the personal factor overcome impersonal facts. Was it Renan who said : " Le plus grand peintre n' apercoit dans le monde que ce qu'il aime y voir ; it y a une preference au fond de chaque talent? "