Painting Nature |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Page 02 / 14

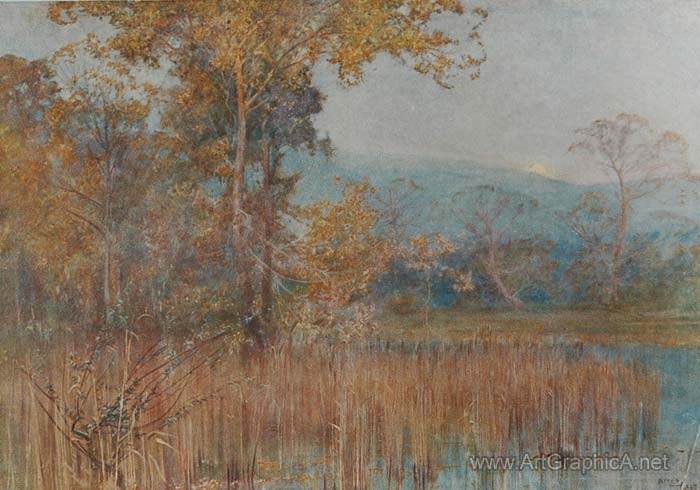

LANDSCAPE PAINTING IN OIL COLOURCHAPTER IATTITUDE TOWARDS NATUREYOUR attitude towards Nature should be respectful, but at the same time confident. One should love Nature without giving up one's authority. Do not grovel before Nature -- be a man. Stand to your work, and draw and paint from your shoulder in a confident and manly fashion, feeling that you know what you want, and go for it fearlessly, with a keen observation of Nature. Look long at her, consider carefully, and then, when you have made up your mind, express it confidently and in a manly fashion. Do not go to your work as a task, but as a labour of love. One can detect at once the work the painter attempted with an immature knowledge of Nature ; it is not confident and spontaneous, and if he gets, after great labour, something approaching what he wanted, the evidence of his fatigue is apparent. There is no fatigue in Nature. Nature expresses life with a curious and interesting sense of directness. Although we know there are millions of years behind her simplest developments, yet the result is one of apparent ease, a spontaneous and direct effort. So should your Art be, and it is in this respect it should resemble Nature, revealing an infinitely higher quality than the mere imitation of her surface. Paint as if you had the authority of a man, as though all Nature was made for your use, to be at your disposal. Respect the power which lies behind Nature, and if you respect that, it should keep you from the abuse of Nature, and should bring you into closer touch with the great purpose of its being.  Misty Moonrise. Painting Nature. Build up your picture from the broad masses ; don't finish your trees, or your sky, or your distance first. Work on them all at the same time, keeping them in tone like an orchestra. Keep them all in hand like a musical conductor. Have no false notes, no discordant line or colour. Keep in your mind that you must not be ruled or unduly governed by what you see in Art, but by what you see in Nature. Don't form altogether your ideas of Art from pictures, but from Nature. That is your business. The value of tradition in Art is a question we will not discuss here. It is sufficient for one to get into touch with Nature and be in the most intimate sympathy with her. Take every means in your power of learning more of her, and her methods of work, and her possibilities of expression. Learn all about her, what she will do under any and every effect. You will not succeed in finding out all the possibilities of her expression of beauty in her many moods, but you will, in the course of time, know a great deal that will be helpful. For instance, in taking the trouble to paint a sky every morning, at the same hour, for a few weeks, no matter what the sky is, at the end of the time you have learned something more of the sky than you can read in the latest scientific book ; and so of other things. I also find that if I draw a tree every day for a month, I have gained some knowledge of the peculiar characteristics of trees that had escaped my observation before, and it is of no use knowing the names of the bones and muscles of the body unless you know what they will do in action. One ought to know a tree so well that one can alter its form to suit the purpose of one's composition without the slightest loss of its characteristics; just as a figure painter should know anatomy so well that he can put his figure in action without a model, with as much case as he could draw it in repose. This knowledge gives one confidence and authority, or, shall I call it, faith in oneself? If you desire to transpose your trees, for instance, to put in some that arc growing outside the area you have selected to paint, if you feel that such arc necessary for the composition of your picture, you have as much right to put them there as the yokel who planted them where they are growing some fifty years before. But you have not the right to do so if you do not know sufficient of their characteristics; you will be found out, for they will look as if they were artificially put in. But if you know them well enough, their requirements of soil and situation, as well as their construction and character, they will be right. My point is--get knowledge. Find out first the why and the wherefore of all things. The greater the knowledge of Nature, the simpler and stronger will be your work. You are to build up your landscape with the best of the beautiful materials you can find, not to be led aside from your great purpose by the little things that are not wanted, even if they are beautiful. Go forward in the world with a purpose, a great purpose. You are responsible for your work done, and you only. The material is right ; Nature is as kind to you as she was to Shakespeare. If there is a fault or failure, do not be so mean as to suggest that it was due to Nature. Shakespeare does not tell you what buttons were on the coat of Hamlet, but he does reveal to you the secret of his character. We do not want the buttons and the braid and all the stage properties; we want the living, sentient man, his place in life which makes history. And so with you. You do not want the pretty little things of Nature ; you want the big strong essentials which stir the heart of man, and show that you have felt and seen them and can reveal them to others. Strong men are working in other fields of thought for you, and they look to you for your part to be done well, as you expect the best from them. The architect does not blame his stone. He may build from the same quarry as St. Paul's, and yet the building may be beneath contempt, and so you must know that there is no excuse for you. Nature is for you, as it was for all men. And if you know it as well as the great who have gone, you will be able to tell us something new, as they did, even if it be different. Again, let me impress upon you to approach your work in a manly, confident spirit. Be not ashamed to do the drudgery of constant practice at drawing or sketching. Learn to serve and keep awake. Have your eyes and your heart open, always working. Keep your picture together, a touch here, a touch there; whatever you can correct, do so--here a touch in the sky, there one in the foreground, another in the middle distance. Build up your entire picture as one great whole, one intention ; not in patches of separate interests, but all tending to one purpose and one only, every part being interdependent upon another, that the whole should be sure and certain, as confident as a sketch, and as spontaneous as Nature. There should be no sense of fatigue ; it should appear as if it were simply and easily done. You may have sweated at it, you may have given it weeks of thought, both by day and night ; you may have groaned and writhed in the deepest anxiety, yet the result should be as simple and direct as a beautiful sonnet: that shows your conquest. No more, no less is wanted. You have secured what you wanted, and it is finished. If you have no enthusiasm, and lack courage, stay at home and do other work that befits your temperament. A landscape painter must have enthusiasm, and no shame in speaking of the pleasure he feels in his work. I think it is useful to speak about what interests you most; but be quite sure that you have the sympathy of the person to whom you speak. You need not be ashamed of your calling, for if you knew the innermost feelings of the hearts of others, you might find that you are envied by those who cannot purchase the pleasure you have in following the calling you love best in life.

Next Page

Prev PagePainting Materials Landscape Painting

|

|||||||||||||||||||||