FLEMISH AND DUSTCH SCHOOL OF ART |

||||||||||||||||

|

Page 07 / 09

OIL PAINTING BOOK CHAPTER V THE FLEMISH SCHOOLIf there is no truth in the legend which tells us that Andréa del Castagno murdered a brother artist through whom the Flemish secret had been imparted to him, to prevent the knowledge extending further, there can be little doubt that some painters were jealous of their technical secrets; and for this reason we have to reconstruct from external evidence what appears to have been the methods pursued. To what degree of perfection Jan Van Eyck carried his new-found art can be seen in the [171] portrait-group of "Jan Arnolfini and his Wife." It enabled him to realise a fulness of tone, a variety of textures, and a microscopic completeness that had not been possible in the fresco tempera, or other methods in use prior to the discovery of his varnish oil medium. The white of the ground shines through the semi-opaque light passages, and the draperies and accessories only are solidly covered. The head of a man in a red head-dress by the same master is a gem unapproached. Note the liquid eye and the subtlety of the flesh colouring quite thinly painted. There is probably nothing between the gesso ground and the semi-opaque colour over it. It was to these pictures that the English Pre-Raphaelites turned for inspiration and guidance. There are just two methods for the painting of light which are technically perfect. One is the translucent process of Van Eyck, the other the manner taught in the school of Rubens. JAN VAN EYCK A MAN'S PORTRAIT

National Gallery The eyes in this are worthy of the closest study ; the head is thinly painted on the gesso ground. XXXIX. A MAN'S PORTRAIT. BY JAN VAN EYCK [171] RUBENSRubens broke through the traditions of the earlier Flemings ; his vigorous temperament made him impatient of the constraints imposed by the saving at all hazards of the white negative ground. White pigment becomes with him a very active agent, and he reserves the white and sometimes light-grey ground to secure transparency in his shadows. [172] We are told on good authority that "Everything at first under the pencil of Rubens had the appearance of a glaze only." One of his leading maxims respecting colour, which he repeated often in his school, was that "it was very dangerous to use white and black. Begin painting your shadows thinly, and be careful not to let white insinuate itself into them, as it is poison for a picture except in the lights. If white is ever allowed to dull the perfect transparency and golden warmth of your shadows, your colouring will be no longer glowing, but heavy and grey. The case was different in regard to the lights; in them the colour may be loaded as much as may be thought requisite. They have substance ; it is necessary, however, to keep them pure. This is effected by laying each tint in its place, and the various tints next each other, so that by a slight blending with the brush they may be softened, passing one into the other without stirring them." Few masters of the overpowering vigour of Rubens preserve the same methods throughout their career, and perforce adapt their process to the special demands of varying effects ; but there are certain guiding principles to which they remain faithful, and we may conclude that his brilliancy, and the luminosity that belongs equally to the work of his pupils Van Dyck and Jordaens, who was rather an assistant than a pupil, was largely due to the clear under-painting and the [175] separate superposing of more or less transparent colours. " Chapeau de Paille." Looking carefully at this, we shall find that the flesh was laid in in a high key ; for the head, delicately shaded by the hat, is toned in thin washes over the brighter ground, "The Château de Stein" was first prepared in a warm brown monochrome, the distance in blue and white. The Triumph " Silenus " is in his earlier manner, with much vermilion in the first ébauche. I have a Jordaens similar in colour to this, and there is one head in it, from which the glazes have been rubbed off in the cleaning, showing a white modelling beneath. So solid is the general effect that one would never suspect, save for the white ground discovered, that its rich colour was due to scumbling and glazes. Vermilion is freely, used in the extremities. The " Venus and Mars " on the adjoining wall is on an unusually rough canvas for Rubens. The flesh in it is brilliant, but not much loaded. Its handling can best be studied in the back of the cupid in the foreground and the festoons of fruit. The influence of Titian is evident here, and there is little use of the fresh reds of his earlier work. Rubens returned from Italy, to which country he made repeated and long journeys, with many copies of Venetian pictures and several original paintings by Titian. And while in Spain, he made [176] replicas of the Venetian master's works which had a distinctly chastening effect on his colour. What, however, I wish you particularly to examine and study is a passage in the "Abduction of the Sabine Women," in which is concentrated Rubens's mastery in the painting of flesh. It is in the arms and hands clasped of the woman bending forward near the centre of the picture, which, by the way, is in surface much smoother than the " Venus and Mars," and so allowing of a greater measure of fatness in the handling. Note the warm brown shadows on these arms, the broken touches of light, and then the liquid melting of the scumble over the warmer ground. In this passage are summed up the master's highest powers as a painter of the nude. This liquid opalescence is seen throughout his work, but rarely to such advantage as in these arms and hands. The cool grey under the breast of the central woman in black and loaded gold satin is notable, as is also the obvious imitation of Veronese in the architecture and faintly indicated figures in the background. RUBENS THE ABDUCTION OF THE SABINE WOMEN

National Gallery In the arms and hands of the woman bending forward this master's rendering of flesh is seen at its best.XL. THE ABDUCTION OF THE SABINE WOMEN. BY RUBENS VAN DYCKNow let us go straight to the Van Dyck portrait of " Van der Geest," and we shall see the identical use of this scumble, liquidly and smoothly worked over the modelling of the right cheek and near the eye. The head is one of the greatest achievements [179] of painting and characterisation in existence, and to appreciate thoroughly its beauties it should be copied, in the first instance in brown grisaille, the shadows kept warm. In the second painting, load the impasto on the forehead, nose, and other places where it occurs, with stiff white and a varnish medium; and when this is dry, or nearly dry, paint thinly the colour of the whole, glazing the mouth and separately drawing some of the hair. Note in the grisaille stage how the cheek is lost and found in the white of the ruff, how the blue in the pupil is fused in places into the white of the eye, how in the thin colour stage the scumble is dragged into the dry shadows above and below the brow. There is more to be learnt in the painting of flesh from this picture than from almost any other I know, so luminous is this masterpiece, so rich, so complete. No lips ever breathed in a picture like these. Nor eyes more liquid, except perhaps in the Van Eyck head with the red turban, to which these are not unlike in many respects. No wonder Van Dyck carried this portrait from Court to Court as an example of his power. "The Marchese Cattaneo" has no marked impasto, but was probably prepared much in the same manner. The warm colour is too evenly toned to have been done in any other way than glazing, which can be seen in the interstices of the canvas in the neighbourhood of the chin. [180] In the "Marchesa" the ruff is painted thinly over the dark ground, with solid pigment at its laced edge, and the red of the hair floated into the final glazes of the face. In the small room, which contains some extraordinary drawings by Rubens, is a grisaille composition by Van Dyck of "Rinaldo and Armida" done in asphaltum, black, and white. This is squared off for enlarging. There are similar monochrome studies for portraits in Munich. The whole arrangement for the larger pictures is thought out in these small studies. VAN DYCK CORNELIUS VAN DER GEESTNational Gallery One of the finest examples of his art. XLI. PORTRAIT OF CORNELIUS VNA DER GEEST. BY VAN DYCK [181] THE DUTCH SCHOOLREMBRANDTWe are for the moment less concerned with the overflowing human sympathy with which this greatest of poetic painters has invested every being he has portrayed, than with an analysis of his workmanship ; but as his every touch, every shade, every gesture, is impregnated with humanity, we should do well, while investigating his means of expression, to keep in touch with the spirit inherent in his work. The portrait of himself as a youngish man is smooth, almost polished in surface, for him, tight and detailed in the drawing, fine in colour, but has no signs of the daring use of pigment [182] seen in his later work. Nor is it possible with so much completeness of detail to combine absolute freedom of brushwork. On the other hand, the sureness and vigour he exhibits later in life is the outcome of the knowledge gained by this close application in his earlier studies; and it is well to remember that to attempt to begin where he left off would result in those pretentious daubs that expose all their weaknesses, including the pretensions. The "Portrait of an Old Lady," in the white cap and ruff, is executed in the Rubens manner. Look closely into it and you will find that the burnt siena shadows of the first ébauche are here and there left transparent. The warm over-painting with liquid scumbling is very like that of the Flemish master. It is freely and rapidly executed, and with small brushed the varnish impasto is touched solidly in the lights. The cap, so exquisitely modelled, is in a like manner thinly floated over the dark of the ground and the white of the ruff. Now turn to the "Woman Bathing " and examine the consummate rendering of flesh in the bosom, head, and legs, the riot of fat paint in the chemise, and the rich glazes in the coloured draperies on the bank by the pool. This is certainly a study to copy some day, not so much with the idea of making an exact replica-that would have too restraining an effect-but [185] rather with the purpose of rendering its unctuous properties. The grisaille composition of "Christ before Pilate" gives a clue to the first laying in. "We have now to consider for the following stage the nature of the grey in the legs and head. Extract from them the warm tones and we shall get it. There is a cooler note in the half-tone under the breasts ; with such a grey, and a loaded varnish white, in a full brush, we should paint the shoulders and breast, and the chemise with a very liquid white played wet into a greyer ground, aided with touches of the palette knife ; and then the shadows of the background fairly transparently. Over the whole, when dry, float a golden glaze which should give us some of the qualities of this gem. It is to the varnish glazes that much of its liquidity is due. The small monochrome of a " Crucifixion " has great charm. " The Flight into Egypt " is a slightly tinted monochrome, like several small religious subjects in Munich, which are practically monochromes, with but a few positive colour glazes. " The Jewish Merchant " is of the firmer type of workmanship, with a rare subtlety of modelling in the head. With your half-closed eyes, see how the undulations of its surface are effected by the delicate variations of its tones. An enthusiastic sculptor, when an old man and blind, was often led to that wonderful fragment " The Torso Belvedere " in the Vatican, the beauties [186] of which, denied to his eyes, he would enjoy by caressing with his hands. So with this portrait of Rembrandt one longs to feel with one's fingers to test the apparent solidity of its planes, which were always the chief object of the painter's care ; in itself an excellent lesson, for in this way a comprehensive and large outlook is attained and preserved. Ever keep the big things in view. Simplicity is the greatest virtue, and the last achieved in any art. " The Head of a Rabbi " is again in a more liquid manner. The transparent shadow on the forehead cast by the cap, the blue-grey touches beside the eye, the varnish impasto on the nose and cheek, the cool boundary of the beard against the face, the shadow of the nostril fused wet into the upper lip, are, among many others, qualities of this masterpiece to revel in. The virility of Rembrandt, with his full loadings and broken colour, was something of a shock to his contemporaries, who prized most the suave surfaces to which they were habituated. This looseness became accentuated as he advanced in years, and to a criticism of it the master retorted that he was a painter, not a dyer. At this stage the portrait of an old man with a grey beard and his own with a turban were done. The foreheads are in full light, for he is striving now for greater brilliancy. We see the hard, stiff white through which the firm brush is ploughed ; and always the luscious silver-grey of the underground, [189] which is sometimes, as in the beard of the old man with the red cap, liquidly scumbled in the after stage, the broken glazes finding their way in and around the furrows made by the brush. But the craftsmanship in these is so fine, the modelling so just, the hand so assured, and the surface actually so beautiful, that the centuries have enhanced rather than detracted from their ripeness. Only in the hands of a transcendent genius is such free use of material, backed as it is with vast experience, made possible. The raw white loadings that are thrown at us now, as a make-believe for sunshine, and trowelled over the whole of a canvas, are not of the stuff that Rembrandts are made of. Nor do impastos answer their legitimate end, except as accents or rare variations from the general level, and then only in fitting proportion to the scale of a work in which they are used. When wisely and discreetly left, the deposits of a real, not assumed enthusiasm, fired spontaneously in the warmth of production-then and then only, like the moving passion of the orator, they move us to a real admiration. REMBRANDT WOMAN BATHING

National Gallery strong>The rich and unctuous properties of oil paint have rarely, have perhaps never, been so thoroughly exploited as in this picture. XLII. WOMAN BATHING. BY REMBRANDT REMBRANDT A JEWISH MERCHANT

National Gallery A perfect example of solid modelling produced by subtle variations of tone. XLIII. A JEWISH MERCHANT. BY REMBRANDT [190] CHAPTER VII THE DUTCH SCHOOLFANS HALSTHE newly acquired Family Group by Frans Hals is, except for its vitality, not particularly fine. The confused moving group, like so many of Hals's, is intensely bourgeois. There is a delightful note in the little maid's sparkling face in the foreground, which saves the picture, painted as it is with much Batavian courage. The very dark ground on which it is done, and done thinly, has sobered the tones and induced a blue coldness in the whites. Liveliness there always is in Hals's treatment, with his frank telling lights, separate and undisturbed by any softening process, leaving a masterly and big impression that subtler modelling might well belittle. Remarkable qualities, such as his, bear with them their defects. We may not look for Venetian or Spanish dignity allied to his vivacity-the one is the negation of the other-so we must be thankful for the temperament that could make painted people well-nigh move and talk, and spread around some of the gaiety they had imbibed.[191] That he was at times even grave, we may judge from his picture at Haarlem, where most of his important works are collected, in a large pathetic group of old women. There also is the great canvas of the " Guild of Archers," so brilliant and full of colour and so spirited that it is one of the great portrait groups of the world. But perhaps the most thoroughly enjoyable of his pictures is a portrait of himself and his wife, which for expression and frankness is in its way unequalled. The head of an " Old Woman " here is free, but dulled by its heavy ground. "The Smiling Man," on a lighter background, is fuller, but not well modelled for a Hals ; and you will note that the ground without any covering supplies the middle tones of the hair. There is a small canvas in this gallery by de Keyser, high-toned in the flesh and pure in lighting throughout. Rembrandt owed much to de Keyser, who deserves to be better appreciated. FRANS HALS THE PAINTER AND HIS WIFE

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Frans Hals at his best. XLIV. THE PAINTER AND HIS WIFE. BY FRANS HALS NICOLAS MAESNicolas Maes was a pupil of Rembrandt whose methods are strongly reflected in the life-size group of a woman in red and a man playing at cards ; but his real métier is seen to greater advantage in several small pictures at the National Gallery-interiors lighted from an exceptionally small high window, from which only the chief [194] actors are illuminated. The mystery of the shadow melting away from this concentrated light is telling in the extreme. NICOLAS MAES THE IDLE SERVANT

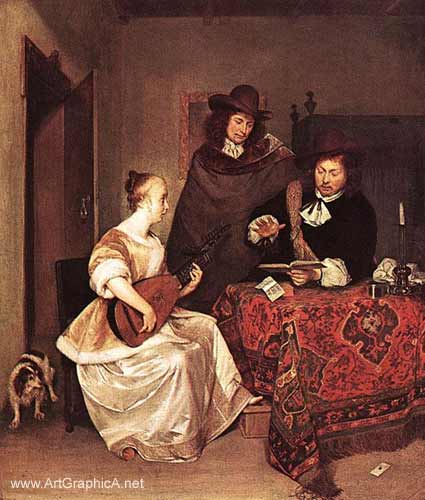

National Gallery A brilliant example of effective lighting. XLV. THE IDLE SERVANT. BY NICHOLAS MAES TERBURG AND METSUIf, as I pointed out, the freedom of Rembrandt's later expression was not compatible with the finish of his earlier portrait, such freedom is certainly not consistent with the polished and minute completeness of a Terburg or a Metsu. " The Guitar Lesson."-The warm harmonious setting of this well-balanced composition, its deliciously manipulated textures, and the suavity of the surfaces gain for this panel the highest place among the works of Dutch genre. With Terburg, Metsu, de Keyser, Hals, and occasionally with Velazquez and many others, the grounds were prepared with varying tones of warm or cool grey evenly laid, graduating to a lighter ochre colour in the lower part, which is to represent the floor, and on this ground incidents, and accidents of light and shade, are thinly indicated, such as the blacks and dark draperies generally. Where this preparation is not much darker than the half-tones of the scheme, the light of the picture does not suffer; but where it is considerably darker, we find that the tonality of a work is affected throughout, and most strikingly in the less solidly touched parts. Look carefully at the head of the lady with the [197] guitar. It is completely modelled and drawn in white and grey, then thinly coloured, the chin and neck almost left, the warmer nose semi-opaquely brushed. It is a key to the master's method. How the finish which we see on the white satin dress was accomplished is inconceivable to any one who knows the practical difficulties involved. It is too well modelled to have been done with a lay figure, so we must conclude that the patient lady sat from early morn till the late evening of a long summer's day without moving ; for, apart from the flat underlying pigment, it must have been painted direct at a sitting-such folds do not fall twice alike. In any case it is a remarkable feat. Metsu probably began much as Terburg did, but finished with rather more solid colour, for Terburg's is a thin manner, and because of this in the latter's " Portrait of a Gentleman " the background tones blacken the flesh. The pigment is not strong enough to resist this dulling action. The tone quality of the black silk over the boots, and the leather of the boots themselves, is altogether admirable, a fine lesson in the management of soft light on black textures. TERBURG

THE GUITAR LESSON

National Gallery Dutch genre at its best. In this picture the prepared grey ground referred to in the text will be seen. XLVI. THE GUITAR LESSON. BY TERBURG JAN STEENThe little Jan Steen of the girl in yellow and blue at a harpsichord, is another perfect performance. [198] The slightly larger panel is by no means representative of the master's best work. There is little need to enlarge on his practice, for in the same room as the Van Dyck grisaille you will have seen a black-and-white by Jan Steen. Although blacker than the monochromes of other Dutchmen-for his greys are a little more metallic than most-this preparation gives a fair idea of the way his contemporaries also set about their work. PETER DE HOOCHPeter de Hooch's interiors and courtyards are crisp exercises in glowing light, but 'are fine pictures at the same time. " The Vermeer of Delft " is another example of subtle lighting. The flesh tints of the girl are over grey. Possibly the glazes have flown, but the play of light on the flat wall is a successful achievement, for it is an extremely difficult task to preserve such flatness in tones receding from a centre of light. The firm " touch " throughout is an excellent example of brushwork. It is the velvety surface of these pictures to which I would particularly draw your attention. The present neglect of the easel picture is without doubt due to the surface coarseness of much modern work, and in the few instances where high finish is attempted there is a lack, except in the hands of [201] very few, of that freshness so fascinating in the best Dutch pieces. We are in too great a hurry, and careless about preliminary preparations both in the direction of the necessary studies and of "what should be the predetermined grounds over which the final painting is done. If genre subjects are to find renewed favour, these Dutchmen, I feel certain, will show the way, and the raw empirical luminists will be left in the impasse to which they have attracted the unthinking. The means should never be more evident than the ability to use them with discrimination and with purpose. Of this the Dutch were conscious, and of this too many moderns are oblivious. The Dutch landscapists evince with the figure painters the same exquisite surface, and although in some instances their conceptions resemble less the light of nature than do more modern landscapes, the general quality is more satisfying and better fitted to be seen on the walls of a room. Their excessive brownness is due to the brown under-painting ; and their depth to a common use of the Flemish glass with a black reflector which replaces the quicksilver of the ordinary handglass. There is an interesting letter in Mr. Hamerton's " Graphic Arts," from the late Sir John Gilbert to the author, which explains the methods of the Dutch landscapists as well as of Rubens, Teniers, [202] and others, from which I shall make a few extracts. He writes :- " The system of monochrome foundation is that of the Flemish and Dutch Schools, and it is as applicable to landscapes as to figure pictures. Rubens got his landscapes in brown all over, so did Teniers, so did the Dutch landscape and marine painters. " They put in all the forms, clouds, distant hill, middle distance, and figures with brown, raw umber, burnt sienna, raw umber and black. Some used warmer browns than others. This work dry, they went all over the canvas with raw sienna, or raw sienna cooled to a kind of dun colour. " The blues of the sky were thinly painted over this ground after it was thoroughly dry. By looking carefully into the landscapes you will see the ground shining through the blue. This gives air and prevents coldness. You will see it hi the clouds, and you will not fail to see it all through the rest of the picture. "It is more apparent as it comes to the foreground, which is, in fact, almost left as at first prepared. "See Teniers, and Rubens, and indeed all of them." Then among other observations he writes :- " In all cases and all their landscapes the monochrome system prevails. You can get the most [203] lovely variety of greys in this way. Scumbling lightly a cool tint over the warm preparation," and so on. Sir John Gilbert Worked in this method, which he had so exhaustively studied, and of which he thoroughly understood the possibilities. He so well explains the processes of the Dutchmen of the Teniers type that there is little need to add more than to observe that, in favouring a warm general tone, they were more concerned with their simple harmonies, than with a faithful transcript of the hues of nature. Nature is, after all, not the only standard by which a picture is to be judged. Although psychologically the painter may not stray far from her-and he must be assured of his power to reproduce her telle qu'elle est before attempting any fantasies on the theme she suggests, technical or moral-allowances must be made for the temperament of the artist, even for his limitations; and we must be equally tolerant of his mannerisms, which I suppose we should define as departures, as subtle variations, from what is actually seen, in favour of a purely personal expression. CHAPTER VIII THE SPANISH SCHOOLVELAZQUEZTHESE considerations naturally lead us on to Velazquez, of all masters the least mannered, in some aspects nearer to nature in his interpretations than any other. In every sense a realist, he stated the large facts with the broadest touch, and boiled them down to their utmost simplicity. This breadth of view was the goal he reached only in his mature years; and in following his development, which is fairly illustrated by the small collection of his works in these galleries, we shall see that he shed one by one the shackles that constrained his earlier manner-constraints, however, which prepared his hand and his mind to understand and to execute, with an unerring draughtsmanship and a just appreciation of values, the masterly painting which places him high up in the first rank of the masters. "Christ in the House of Martha " is an early example of his naïve composition and harsh and heavy treatment ; only in the still life do we realise his promise. "Christ at the Column" is little more than a [207] grisaille on a dark canvas with a light base. Breadth there is in it, but none of the light of his riper efforts. An earlier work than this, I imagine, is the full length of Philip IV., which to an extent recalls the less developed painting of the sixteenth century, when the prejudice against positive shadows in the flesh prevailed. I turn to this, for, hanging as it does as a pendant to the "Admiral Pulido-Pareja," we are able to compare his early with his fully matured outlook and accomplishment- the flatness and thinness of the Philip with the roundness and solidity of the other. The Admiral is bathed in air. The solidifying force of finely contrasted values and subtle colour-contrasts is now the master's secret, which henceforth is to be a model throughout the generations. He now knows that a living illusion is not enhanced by rigid draperies accentuated equally throughout, but that movement is imparted by free handling, that real texture of surfaces was more perfectly suggested by colour and tone-relations than by minute imitation of the passages detached from the general envelopment. The Admiral is a living character whose pose is as determined as his face, which is rendered in very definite planes, and is "flesh and bone," by force of that justness of tone and the weight-giving truth of colour. Let us examine more closely its execution. The ground, as with some of the Dutch masters, is grey, subsequently warmed, [208] graduating to the ochre-coloured floor, over which the whole figure appears to have been painted; for the blacks are thinly imposed on it, and the baton in the gloved hand is again so meagrely touched in as to show the background and the black drapery through it. The cast shadow on the floor is a mere wash of dark over the prepared ground, but nothing can exceed the fascination such qualities have for the craftsman, the full-brushed light on the sleeves, with the few deliberate high-standing impastos resolutely laid on them, and the liquid treatment of the gloves. The picture is a masterpiece of construction, bigness, and tonal relief, a fine example of Velazquez's later direct or nearly direct manner, and this in spite of the doubts expressed by certain critics with regard to its authorship. Those who assert-and there are many-that Rubens, who spent nine months in Madrid with Velazquez at the impressionable age of twenty-nine, exerted no influence on the younger man, cannot have examined with any care either the "Venus and Cupid" or the small "Philip IV." They are distinctly in the Rubens manner, or adaptations of it in the hands of a realist, who very possibly had little sympathy with what he would have considered the mannerisms of the Flemish master. We shall find, on looking closely at it, that the Venus, like the Admiral, is on a toned canvas. The figure is first prepared in white, and probably [211] Indian red and black. In few places is the canvas really lost under the whites. In one place-behind the knees-it is, however, filled-a very wonderful and supple rendering of flesh, completed in the thin glazes and semi-opaque manner of Rubens. This is clearly shown by the subsequent widening of the shoulder through which the background asserts itself. The colour and the glazes on the Cupid are somewhat red, for such a red curtain as his setting usually influences the greys of the flesh towards its complement green. The small " Philip IV." is one of our treasures, and should be copied. It is also painted over a preparation that appears to have been made in white and Indian red, and finished in the Rubens manner. The eyelids, which Velazquez did not at this stage outline as with Van Dyck, show a thin painting over the dark of the pupils, and the pink greys of the flesh point to a use of Indian red both in the ground and the last painting. The " Betrothal " is, of course, a direct colour sketch over a dark canvas, and although very spirited, has none of the brilliancy of the Philip or the Venus, which are better calculated, because of their pure white preparations, to resist the darkening action of Time. In "The Boar Hunt," the landscape seems to have been laid in in brown over a warm ground, which, by the way, shows through the half-tones of the horses. The more solid lights have resisted its influence. The most interesting portions of [212] this fine picture are the foreground groups of men and hounds, where the beauty of impasto is brought home to us as in few other works. To be thoroughly understood and appreciated, Velazquez must be seen in Madrid at the Prado Gallery, in which magnificent collection are the two portraits accompanying these notes. "The Sculptor" is in a similar light to the Admiral, and has much in common with it, but the colour is fairer. The oneness of the head, the perfect construction of the forehead and the planes of the temple, the eye so absolutely in its setting, the complete finish of the ear, and the freely touched beard, are among a few of its excellences. The "Dwarf "in the original is highly and smoothly finished, not detail finish, but of a homogeneous surface, which is the higher order of completeness. It is soft and pulpy. Note the part played in the roundness of its modelling by the delicate tone running down by the nose, on the shadow side, the local colour of the tip of the nose, and thé solidity and learned drawing of the lighted eyelid. Nothing could well be finer than the rotundity of this head or its fleshiness, to which the melting edges of the shadows into the lights contribute so much. VELAZQUEZPHILIP IV., KING OF SPAIN

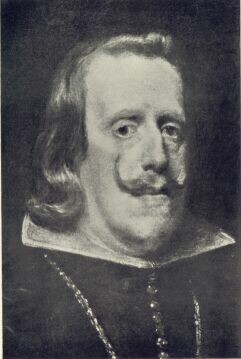

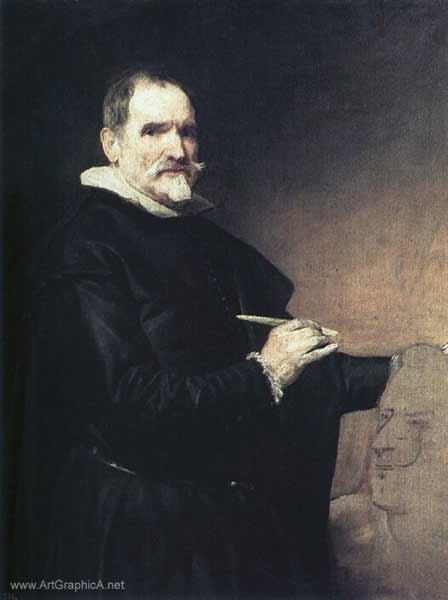

National Gallery This exquisite portrait and the Rokeby Venus appear to show the influence of Rubens on Velazquez. XLVII. PHILIP IV., KING OF SPAIN. BY VELAZQUEZ VELAZQUEZTHE SCULPTOR

Gall. del Prado, Madrid Extreme breadth and subtle modelling combined. XLVIII. THE SCULPTOR. BY VELAZQUEZ VELAZQUEZ THE DWARF

Gall. del Prado, Madrid One of the finest examples of big though subtle modelling. XLIX. THE DWARF. BY VELAZQUEZ RIBERA"The Dead Christ" by Ribera is, like all this master's work, a fine technical achievement, if somewhat heavy in the shadows. His vigorous [215] use of solid pigment in the lights has in it great virility. ZURBARANAnother Spaniard of great distinction. The cowled head of "The Monk at Prayer" is broad and big in feeling. The shadowed face, with its firmly modelled nose, is a superb study, and the gown fine in texture and large in arrangement. " The Nativity " was at one time ascribed to Velazquez. The draperies are certainly not unlike his, but whoever did it produced a work of great merit. The lighting is beautiful, and the final painting is solid and direct. EL GRECO" Christ at the Temple " bears a curious resemblance in colour to Bassano. The figures are attenuated and the heads very tiny. El Greco is said to have much influenced Velazquez. MURILLO"The Infant St. John and the Lamb" is one of his best works-solid, if bituminous. "The Beggar Boy " is good in character, but lacking in substance. His other pictures here are not of the first rank. GOYAIn his portrait of a gentleman he is not unlike Gainsborough, whose work he admired.

|

||||||||||||||||